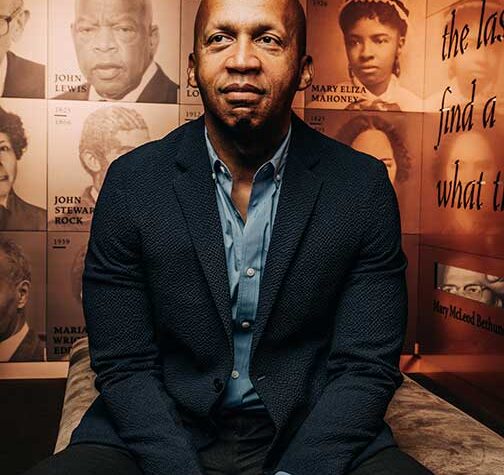

There’s a courtroom scene in Just Mercy, the widely acclaimed film based on the bestselling book by Bryan Stevenson, in which the lawyer fights for a case to be dropped against an unjustly accused Monroeville, Ala. black man. In the argument, the lawyer played by Michael B. Jordan forcibly proclaims: “That’s not law. That’s not justice. That’s not right.” Jordan, playing Stevenson, wins the case and Walter McMillan, who had been sentenced to die for murder despite overwhelming evidence proving his innocence, is freed. Those words uttered in the courtroom symbolize the work of Stevenson, the founder and director of the Equal Justice Initiative(EJI) in Montgomery, Ala. The non-profit law office and human rights organization is dedicated to exonerating innocent death-row prisoners, eliminating excessive and unfair sentencing, confronting abuse of the mentally ill, and aiding children prosecuted as adults.

Forged in Faith. Stevenson was born and raised in Delaware to a family with a long faith tradition. He said that faith, in fact, is what gave him the strength to attain dreams that seemed impossible as a child growing up in segregated schools and society. “Without faith, it was impossible to imagine that I could be a lawyer,” he said. “Faith is all about affirming the importance and legitimacy of believing things even if we haven’t seen them happen before.” Stevenson went on to graduate from Harvard Law School and has argued cases in front of the United States Supreme Court. He moved to Atlanta after receiving his law degree and joined the Southern Center for Human Rights, then was appointed to run the Alabama regional office for the organization. In all of his work, Stevenson leans on the faith of his growing-up years in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and points especially to the words of Micah 6:8 as his guiding principle. Its words– “He has shown you what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God”—were instilled in him by the church. “We took the words of Micah seriously,” he said. “What does God require of us? The answer is to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly. We lived that out, and I came to realize that the absence of justice and mercy have very much implicated us as a society. God calls us to be agents of mercy.” When funding for the Southern Center for Human Rights dried up, Stevenson founded the Equal Justice Initiative to expand his work on behalf of the poor, incarcerated, and condemned. His time in Alabama, he said, has reinforced in him the importance of living in faith. “Being in Montgomery, I’m fully aware that I’m standing on the shoulders of people who had enough faith to make changes happen,” he said.

Spreading the Word. One of Stevenson’s most important roles is that of educator. Any conversation with him starts with the communication of facts–statistics and numbers that can be overwhelming, but that strongly state the need for incarceration reform. “For much of our history we have had around 200,000 incarcerated individuals, but in the 1970s it changed in a radical way and we went from that 200,000 to 2.2 million,” he said. “And we now have the highest rate of incarceration in the world, with 5% of the world population and 25% of those in prison.” He added that 70 million Americans have criminal records and that there’s been an increase by 800% of incarcerated women; especially alarming is the reality that 1 in 3 black boys, 1 in 6 Latino boys, and 1 in 15 boys in general are expected to spend time in prison during their lifetimes. While Stevenson said that there are plenty of legitimate prison convictions in the country, what stands out is unnecessary incarceration for a variety of reasons–excessive punishment for smaller crimes, undue imprisonment for drug convictions, and incarceration for individuals with mental health issues. “This great increase in incarceration doesn’t really correspond to an increase in crime,” he said. “We need to shift our focus and give people a chance to recover. Our punitive program has made that harder.” Stevenson added that over incarceration has a huge impact on communities–especially poor communities– in the United States. “It’s important for us to recognize this is a central issue in American life and that affects millions of us,” he said. “It’s become a critically important issue not just for family, but also for economics.” Through the EJI, Stevenson and other lawyers fight cases and also work at educating the public on such issues. “Learning is an action item. It’s something you can commit to it,” he said. “We have daily calendars that tell the history of racial inequality and other issues. Our website teaches about slavery, reconstruction, and so forth. That kind of education can be transformative.”

The EJI also operates The Legacy Museum and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, both located in Montgomery, which work to educate visitors on the legacy of injustice and inequality and the fight for changes in society today. The museum uses exhibits to educate on the “slave trade, racial terrorism, the Jim Crow South, and the world’s largest prison system”; the memorial honors the 4,075 African-American men, women, and child victims of systematic hanging, burning, and other torturing in the United States. Stevenson believes that the nation still needs to experience moments of “truth and reconciliation” about its past and believes such educational tools can help that happen. “We shouldn’t fear the discussions of race and justice, because I think there’s something better for us in America,” he said. The museum and memorial have been recognized for their innovative and powerful ways in educating, with Town and Country saying it “should be a requirement” for every American to visit.

Just Mercy. Stevenson’s work became widely known after the publication of his memoir, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, in 2014. It recounted his years as a lawyer and focused on telling in alternating chapters about his efforts to overturn Walter McMillan’s wrongful conviction and his work on other cases. McMillan had been convicted in 1987 and sentenced to death (despite a jury’s recommendation of life imprisonment) for the murder of an 18-year-old girl in Monroeville, Ala. Stevenson won the case against McMillan after bringing to light police coercion and perjury. The book was a New York Times bestseller and won many awards including the 2015 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. The 2019 movie adaptation of the book starring Jordan, Jamie Foxx, and Brie Larson was met with widespread acclaim and brought Stevenson’s work to the forefront again.

Focus on the Future. As time has gone by, Stevenson’s work and that of the EJI have evolved. His most recent efforts have focused on the plight of America’s vulnerable populations–the poor, mentally afflicted, and children–and how they are unfairly incarcerated. “We’ve been doing more work with children, because of the toll the system puts on them. In the past, the term ‘super predator’ has been used even on children,” he said. “I’ve represented 9- and 10-year-olds who were classified as that.” He said that it’s “unhealthy, unwise, and immoral” to not realize that children need special protection. One of the cases he’s argued in front of the U. S. Supreme Court included a landmark 2012 ruling that banned mandatory life-imprisonment-without-parole sentences for children 17 or younger. “We are judged by the way we take care of our most vulnerable population,” he said. Stevenson admits that his work can sometimes be overwhelming, but that he lives in hope for what’s to come in the country. He’s encouraged by the newfound recognition that “there are too many people in our jails,” from figures on both the left and right sides of the political spectrum and adds that his faith energizes his work. “My faith convinces me that no one is beyond hope, no one is beyond redemption, and no one has lost their value,” he said. “I definitely believe we can get to a better place.”

Cheryl Sloan Wray