Have you ever driven on Demonbreun Street, James Robertson Parkway, or Donelson Pike, or passed an exit to Charlotte Avenue or the town of Charlotte on I-40? Who in the world were Robertson, Demonbreun, and Donelson? How did a lady named Charlotte have a street and a town named for her? These names reach back to the founding days of Nashville.

When America’s founders signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, a group of pioneers were living in the Watauga settlement of East Tennessee. After purchasing land from members of the Cherokee Nation, some of them prepared to begin a new settlement in the area around French Lick in Middle Tennessee. That new settlement would one day become Nashville.

Those Watauga pioneers believed that an overland route from Watauga to French Lick would be difficult for the women and children, so they divided into two groups. James Robertson would lead most of the men and older boys on an overland route over the Cumberland Mountains to French Lick. Donelson would remain at Watauga with some of the men while they built 30 flatboats to bring the women, children, and enslaved people by water. Among those who waited were James Robertson’s wife, Charlotte, and John Donelson’s daughter, Rachel. Rachel would one day marry Andrew Jackson, who became our seventh president.

The Robertson party set out in the fall of 1779, driving their cattle before them. Robertson planned to build a temporary settlement on the southern side of the Cumberland River, but their route took them to the north side. Robertson wondered how they would cross the river. Cold weather solved the problem. The river was frozen solid, so the pioneers and their cattle walked across the ice. This was the same cold winter when Daniel Boone established Boone’s Station in Kentucky. The Middle Tennessee settlers reached their destination on the same day Boone reached Boone’s Station: Christmas Day, 1779.

The men and boys began building Fort Nashborough, expecting Donelson’s group to arrive in January. They soon began to venture away from the fort to build cabins for their families. They were in constant danger of attack by members of Native Nations who did not agree with the sale of their hunting lands.

Donelson and his party did not arrive in January or February or even in March. None of the settlers had ever traveled to Middle Tennessee by water. They were only guessing that it was possible. Due to delays in building the flatboats, Donelson’s group did not even leave Watauga until December. The boat travelers had terrible difficulties along the way. Native Nations attacked them. Some of the travelers contracted smallpox. They suffered through the treacherous waters of the Muscle Shoals in what is now northern Alabama.

Robertson and Donelson had believed that the Tennessee River flowed near French Lick and that the settlers could easily travel overland from the river to the new settlement. They were badly mistaken. Their route took them across what is now northern Alabama and through West Tennessee and Western Kentucky all the way to the Ohio River. They had to paddle against the Ohio’s current east to the Cumberland River and then paddle against the Cumberland River’s current to French Lick. They did not arrive until April after traveling 1,000 miles.

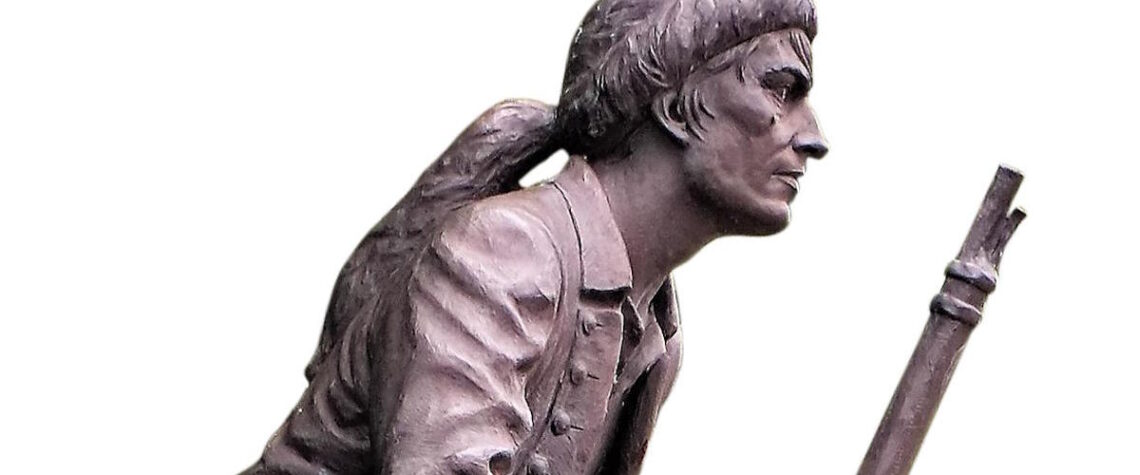

When the Robertson and Donelson parties arrived at French Lick, French Canadian longhunter Timothy Demonbreun had been hunting in the area for several years and had lived there for a brief time. Demonbreun was from a noble family in Canada, was a veteran of the American Revolution, and served as Lieutenant-Governor of the Illinois Territory. Soon after the establishment of Fort Nashborough, Demonbreun moved to the area permanently.

The Marquis de Lafayette, the French nobleman soldier who came to America to aid our cause in the American Revolution, visited Nashville in 1825 on his grand tour through America. During a dinner in Lafayette’s honor, Demonbreun was toasted as “the grand old man of Tennessee and the first white man to settle the Cumberland country.” Demonbreun died the following year. A Nashville newspaper reported: “Died, in this town on Monday evening last, Captain Timothy Dumumrane, a venerable citizen of Nashville, and the first white man that ever emigrated to this vicinity.”

Now when you see those place names, you’ll know that they honor the brave founders of Nashville, Tennessee.

Charlene Notgrass, her husband Ray, and their children founded Notgrass History in 1999. They publish history curriculum used by homeschooling families across America. Charlene is a descendant of Timothy Demonbreun and of Moses Winters, who traveled overland with James Robertson, and of Moses’ wife, Elizabeth, who traveled by flatboat with John Donelson. The Winters settled in Robertson County, which was also named for James Robertson. Charlene was born there and grew up in nearby Ashland City.

Charlene Notgrass

Photo Caption: This statue of Timothy Demonbreun is by the Cumberland River near the site of the reconstructed Fort Nashborough in Nashville. Sculpted by noted Nashville artist Alan LeQuire, it was erected in 1996. Photo by Charlene Notgrass.